Key Points (TL;DR)

- Indexes are a tradeoff between space and time. They are useful for speeding up queries on columns that are frequently queried on, but they take up disk space and need to be maintained.

- Indexes can be compound, i.e they can be a combination of two or more indexes.

- BigQuery is extremely good at text search, and its search index works differently from Postgres’ search index.

- BigQuery’s search index also works on JSON data (examples provided in the article) and on arrays, which is not the case for Postgres.

- PostgreSQL’s full text search uses a Vector Space Model (VSM), which represents documents as vectors in a multi-dimensional space. It also uses a different indexing strategy from BigQuery’s search index.

Building optimized analytics applications: Optimizing for Search

This is the second installment in the series on building highly optimized analytics applications. In the first article, we looked at a simplified anatomy of a modern day analytics stack, and about optimizing queries at the very bottom of the stack, i.e the database. This articles will shift the focus up the stack, by looking at what search indexes are and how they can be used to optimize search queries.

Background: The case for indexing

A famous axiom in the world of optimiztion is the no free lunch theorem which goes:

It follows that if an algorithm achieves superior results on some problems, it must pay with inferiority on other problems.

In other words, there is no single search algorithm that is optimal for all problems. A database considers from a definite space of potential candidate solutions, and chooses the best one. These candidate solutions each relies on a different set of assumptions, and underpins a different set of tradeoffs. We spoke about the index scan in the previous article, and the implementation of such an index scan is an example of such tradeoffs, i.e the tradeoff between space and time.

A quick primer on indexing

We dived into full investigation mode, looking at the data analysts’ queries, and we realize that most of the slow-performing queries are on columns that are text-based. Perhaps the name column, or the stack (the tech stack of each registered user on our platform) column. The data analysts complaining about slow queries overwhelmingly came from the consumer insights team who often had to query textual data, and sometimes JSON data. These discoveries take us down the search index rabbit hole.

Supposed one data analyst on our team is interested in finding all users with the name “Sam”. The naive approach would be to scan through the entire table of users, and check if the name of each user is “Sam”. This is called a sequential scan, and is the most basic form of a table scan. The time complexity of a sequential scan is O(n), where n is the number of rows in the table. In the worst case scenario, the entire table needs to be scanned before the query can return a result set containing all users with the name “Sam”.

With an index, we’re trading off space for time. We do so by first constructing an index, a fancy term for what is essentially a sorted list of all the values in a columm (in our case, the name column of the user table). This index maps each value in the column to the corresponding row id of the user with that name, thus significantly reducing the number of rows that need to be scanned. Instead of scanning from the first row to the last, our optimization allows us to jump directly to the row that contains the name “Sam” and then scan from there.

Prescription without diagnosis is malpractice. We further investigate our analytics workload and realize that, in addition to name, data analysts from the consumer insights team are also often querying on the age column, we can further optimize our index by adding an index on the age column.

Consider the following query:

SELECT * FROM user WHERE name = 'Sam' AND age = 30;With the index on the name column, we can jump directly to the row that contains the name “Sam”, and then scan from there. With the index on the age column, we can jump directly to the row that contains the age 30, and then scan from there (since the index is sorted) to the point where the age is no longer 30.

This is called a compound index, and is a combination of two or more indexes.

So far, so good.

In fact, in practice this search process also involves a few other optimizations, such as the use of b-trees and hash tables to further reduce the number of rows that need to be scanned.

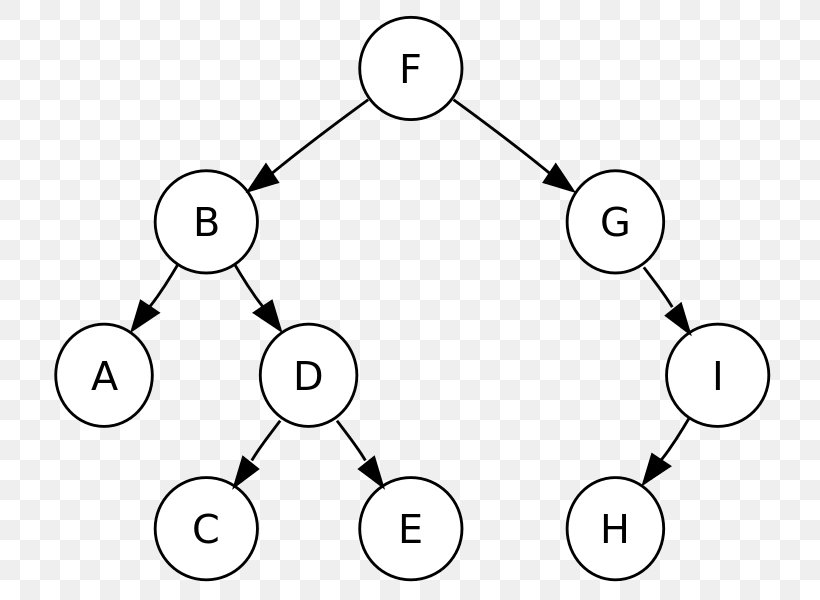

In the binary search tree above, the root node is “F”. To find the customer “Daenerys”, we check if the initial (“D”) comes before or after this letter “F”. Since it comes before “F”, we discard all the nodes to the right of “F”, and shrink the search space to the left.

If “F” is the median letter in our dataset of customers, we are essentially discarding half of the dataset with each iteration. By the second iteration, we have reduced the search space to 1/4 of the original dataset.

This applies equally to numbers as well. Supposed we start with a node that is the median age in our dataset, we are discarding half of the dataset with each iteration, thus arriving at the correct node in O(log n) time.

Caveats of indexing

So indexing is immensely useful, and is the closest to a free lunch that we can get, but it is not without its caveats.

First, indexes are not free. The index structure, and the indexed data both take up disk space, and they need to be maintained. This means that every time a new row is inserted into the table, the index needs to be updated. This is a tradeoff that we need to make, and it is up to you, the analytics engineer, to determine if the tradeoff is worth it. If you present this tradeoff to a management consultant, you will hear these being described as a matter of “cost vs benefit” or “opportunity cost”.

Here are how I reason about this tradeoff:

- If the index is small, and the query is very selective, then the index is worth it.

- If read queries are a lot more frequent than write queries, then the index is worth it since your indexes are not updated as frequently as it is queried.

- If the index is large, and the space is limited in your environment, then the index is not worth it.

- If the speed up (using the query planner to determine the cost of the query with and without the index, a lesson we learn in our previous article) is not significant, then the index is not worth it.

These are general guidelines, and in a business critical environment, you should have your data engineering teams and consultants run regression tests and benchmarks to determine if the index is worth it.

Setting up an index: Practical considerations moving from PostgreSQL to BigQuery

In this section, we will look at how to set up an index in PostgreSQL, and how to use the query planner to determine if an index is worth it. To fully appreciate the benefits of indexing, you might need to set up a database with a large amount of data to test your queries on.

Here is an example of setting up an index in PostgreSQL:

CREATE TABLE users (

id SERIAL PRIMARY KEY,

name TEXT,

email TEXT,

age INTEGER

);

CREATE INDEX ON users (name);Recall from the previous article how we can use the EXPLAIN command to see the query plan for this query:

EXPLAIN SELECT * FROM users WHERE name = 'Sam';This code looks simple enough, but it is actually quite a considerable amount of work for the database; Once an index is set up, the query planner will use the index to determine the best way to execute the query, taking into account multiple factors such as the size of the table, the size of the index, the number of rows that match the query, and the number of rows that need to be scanned.

But if you’re following the scenario we have set up at the beginning of this series, you’d have guessed it: These are amazing features that matter greatly on our old PostgreSQL database, but are not available on BigQuery.

We’ve established in the first article that BigQuery uses a proprietary columnar storage format, and that each query is a full scan of the table.

However, as we’ve also seen in the previous article, BigQuery does have a few features and innovations of its own, and one of them is just about the perfect tool for searching through text (hardly surprising, given that Google is the company behind BigQuery).

Search Index on BigQuery

BigQuery has a feature called search index, which is essentially a full text search engine that allows you to search through text columns in your table. Much like how regular indexes act as a sorted list of values in a column, search indexes act like a table where one column is the text that you want to search for, and the other column is the row id of the row that contains the text (“where in the dataset does this word appear?”).

BigQuery comes with a pair of text analyzer to choose from, and they control how data is tokenized for indexing and searching. The default, LOG_ANALYZER, works well for machine generated logs (eg. web server logs, application logs, system logs, etc) and has its own special rules around tokens (“words”) that are frequently observed in these kind of data, such as IP addresses or emails. The other analyzer, NO_OP_ANALYZER is a simpler analyzer that does not do any tokenization or normalization, and is useful for searching through text that is already tokenized.

This analyzer breaks a search query like “samuel@supertype.ai” into the following tokens: “samuel”, “supertype”, “ai”, and so it is able to help us find a person just by searching for his/her first name, for example.

Here’s an example of creating a search index in BigQuery (simplified from the actual schema we use in Supertype Collective):

CREATE TABLE dataset.nominations (

id INT64,

name STRING,

email STRING,

blogId INT32,

affiliations JSON

stack JSON

);

CREATE SEARCH INDEX search_index

ON dataset.nominations (name, email, affiliations, stack);Notice that we are indexing on the STRING and JSON columns, and not the integer columns. If we have specified ALL COLUMNS, BigQuery would create a search index on all STRING and JSON columns in the table as well.

If we prefer to apply the search index using the NO_OP_ANALYZER, we can do so by specifying it in the OPTIONS parameter:

CREATE TABLE dataset.nominations (

id INT64,

name STRING,

email STRING,

blogId INT32,

affiliations JSON

stack JSON

);

CREATE SEARCH INDEX search_index

ON dataset.nominations (ALL COLUMNS)

OPTIONS(analyzer='NO_OP_ANALYZER');All new columns added to the dataset.nominations table automatically gets indexed as the search index was created with ALL COLUMNS instead of explicitly named columns.

Consider the following table named nominations (again, adopted from Supertype Collective):

+-------------------+-------------------------+------------------+

| name | email | stack |

+-------------------+-------------------------+------------------+

| Gerald Bryan | gerald@supertype.ai |{"1":{"mobile":["iOS","Android","Swift"]},"2":{"database":["SQL Server", "SQLite"]}}|

| Taylor Swift | taylor@celebrity.com |{"1":{"Data":["Shiny (R framework)","Scikit-Learn"]},"2":{"frontend":["JavaScript","NextJS"]},"3":{"backend":["Express","NodeJS"]}} |

+-------------------+-------------------------+------------------+We can issue the following query, written to demonstrate searching over single columns, multiple columns, and the whole table, respectively:

SELECT

SEARCH(email, 'supertype') AS email_supertype,

SEARCH((name, stack), 'swift') AS name_or_stack_swift,

SEARCH(nominations, 'swift') AS all_columns_swift

FROM nominations;The result of the query is:

+-------------------+-------------------------+------------------+

| email_supertype | name_or_stack_swift | all_columns_swift |

+-------------------+-------------------------+------------------+

| true | true | true |

| false | true | true |

+-------------------+-------------------------+------------------+Indexing for text search in PostgreSQL

Searching over textual data like the examples illustrated above are becoming increasingly common in the current landscape of enterprise analytics and data science. So much so, that many databases, PostgreSQL included, have started to include full text search features in their core product.

PostgreSQL full text search similarly allows you to search through text columns in your table, and its parsers come with a variety of tokenizers to choose from. Where its similarity to BigQuery’s search index ends though, is in its implementation. PostgreSQL uses the Vector Space Model (VSM) where each documents and queries are converted into vectors of terms and their frequencies, and the similarity between the two vectors are calculated using a scoring function. This is a very powerful and flexible approach, but it is also very computationally intensive, and might not be always feasible (“no free lunch”).

The ts_parse() function is used to tokenize a string into a vector of terms (tsvector), and the ts_rank() function is used to calculate the similarity between two vectors. The ts_rank() function takes in a vector of terms and their frequencies, and a vector of terms and their weights, and returns a score between 0 and 1. The higher the score, the more similar the two vectors are.

SELECT ts_parse('default', linkedin)

FROM profile

LIMIT 5;Produces:

ts_parse

----------------------

(1,in/chansamuel/)

(14,https://)

(5,www.linkedin.com/in/aurellia-christie-059892179/)

(6,www.linkedin.com)

(18,/in/aurellia-christie-059892179/)On the left is the token ID for the term, and on the right is the term itself. Interestingly, in older versions of PostgreSQL the term https:// would have been tokenized into two tokens, https and ://. The current version, with the default parser, does a more reasonable job of tokenizing the terms in our example.

Using these parsers, we convert documents to the tsvector format for indexing. When we issue a query, the search configuration we specified will also convert this query into vector form.

It is also noteworthy that PostgreSQL parsers do not work on its jsonb data type, and so we have to convert the json column to TEXT before we can use it in the ts_parse() function.

SELECT ts_parse('default', stack::TEXT)

FROM profileand the resulting output would look like (cleaned up for brevity):

ts_parse

(1,database)

(2,sql)

(3,server)

(4,sqlite)

(5,frontend)

(6,react)Once we’ve done the necessary processing and have our textual data in the tsvector, we can then use one of the two index types provided by PostgreSQL, GIN(Generalized Inverted Index) and GIST(Generalized Search Tree). The GIN index is a general purpose index that is optimized for searching over a single column, and the GIST index is a general purpose index that is optimized for searching over multiple columns.

CREATE INDEX profile_gin_index

ON profile

USING gin (ts_parse('default', linkedin));My thoughts on GIN vs GIST, with the caveat that my knowledge is limited to the analytics work load I have encountered so far, is that GIN is generally the recommended option because it is more facilitates more efficient searching over a single column at the expense of slightly slower inserts and updates (because it has to update the index for every row). The creation of the GIN index is also slightly slower than the GIST index as it incur more document processing overhead up front, but the tradeoff is we’ll have a efficient search and now ready for the full text search queries.

Why Index vs fully featured search engine implementation

I cannot bring this chapter to a close without mentioning the elephant in the room: why would we want labour over a search index when we can use a fully featured search engine like Elasticsearch or Solr?

The answer is hinted throughout the article — it is all a tradeoff. Building and maintaining a search engine is a lot of upfront work, and definitely not trivial. You can run a full blown instance of Elasticsearch (I have multiple videos on Elasticsearch on my YouTube channel) in relatively little time, but keeping the index up to date with your data requires an additional layer of engineering complexity if all your company requires is for their data analysts to be able to search through their data using rather routine ad-hoc queries in a familiar SQL-like syntax.

Closing: If you’re not indexing, you’re not trying

At its core, indexing is a way to make data in your database more accessible and searchable to avoid resorting to more exhaustive and expensive operations like a full sequential scan. In the scenario we laid out at the beginning of this series, our analysts are complaining about the slowness of their queries, and we investigate their most commonly run queries to strategize on an indexing strategy.

We found that the slowest queries are often text search queries, on columns that were not indexed. We then proceeded to index the columns that were most commonly searched, using either the BigQuery search index or PostgreSQL full text search features (along with either the GIN or GIST index).

This moves us up the analytics stack, albeit incrementally, and with our implementation of the search index, we are able to (temporarily) hold off from having to implement a full blown search engine like Elasticsearch or Solr. Maybe we’ll get to that in a future article, but for now, we’re happy that the data science team can finally run their queries without finding excuses for lengthy coffee breaks.

This article is part 2 of an ongoing series on building optimized data analytics infrastructure.